Grants to NFPs to deliver intellectual property (IP) to a customer – Does AASB 15 or AASB 1058 apply?

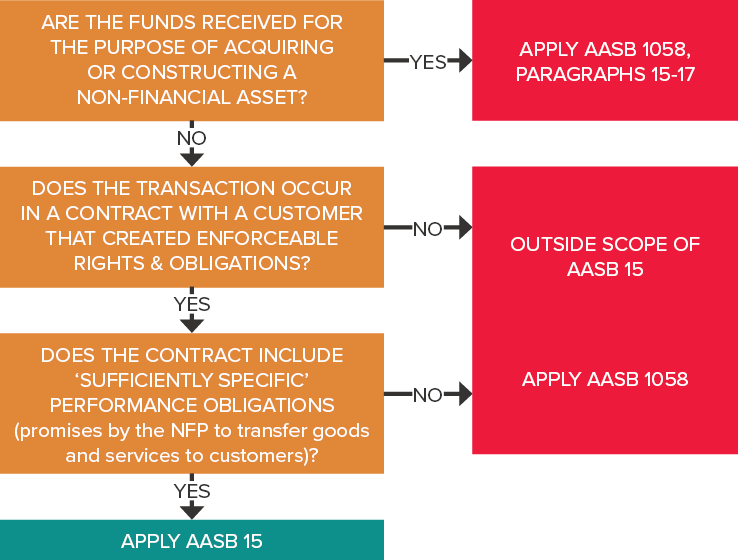

Grants and other donations received by not-for-profit entities (NFPs) can only be recognised as revenue under AASB 15 Revenue from Contracts with Customers if there is an enforceable contract with a customer, and that contract contains ‘sufficiently specific’ performance obligations. Otherwise, income is recognised immediately under paragraph 9 of AASB 1058 Income of Not-for-Profit Entities.

Please refer to previous Accounting News articles for more background information on how to assess whether:

- The transaction occurs in a contract with a customer that creates enforceable rights and obligations (November 2018), and

- The contract includes ‘sufficiently specific’ performance obligations (February 2019).

In this article we examine how a NFP receiving a grant to deliver intellectual property (IP) to a customer determines if it has ‘sufficiently specific’ performance obligations.

If my entity performs research activities, which Standard do I apply when accounting for grants received and when do I recognise revenue?

If we conclude that there are ‘sufficiently specific’ performance obligations, then the grants received will be accounted for under AASB 15. If the performance obligations will only be satisfied in a future reporting period, a contract liability will be recognised under AASB 15, with revenue recognised when the performance obligation is complete. However, if the research contract does not create ‘sufficiently specific’ performance obligations, then income is recognised immediately under AASB 1058, paragraph 9.

AASB FAQ No. 5

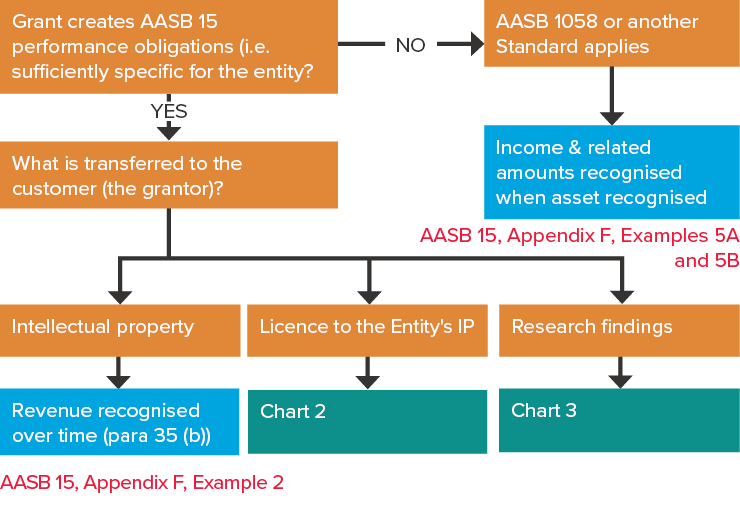

The flow chart below is extracted from FAQs issued by the Australian Accounting Standards Board (AASB) in August 2018. Chart 1 of FAQ No. 5 summarises the required thought process for determining the appropriate recognition of income from grant contracts for different types of research activities, based upon what is being transferred to the customer, i.e.:

- Intellectual property (IP)

- Licence to use the NFPs’ IP, or

- Research findings.

This month we consider the first aspect, where IP is transferred to a customer. In future newsletters we will look at whether AASB 15 or AASB 1058 is applied when there is a transfer of a licence to use IP, and transfer of research findings.

Chart 1 extracted from AASB FAQ No. 5

Chart 1 extracted from AASB FAQ No. 5

You can see from the above that if the grant contract does NOT create enforceable rights and obligations, any income received is recognised immediately when the related asset is received under the grant contracts (for example, cash).

If intellectual property (IP) is being transferred to the customer, does AASB 15 or AASB 1058 apply?

The above flowchart points to AASB 15, Appendix F, Example 2 to demonstrate how we arrive at the answer. Below is an extract of the Fact Pattern for Example 2.

AASB 15, Appendix F - Example 2 – Fact Pattern

University A receives a cash grant from a donor, Road Safety Authority B, of $1.2 million to undertake research that aims to observe and model traffic flows and patterns through black-spot intersections and to develop proposals for improvements to the road system.

The terms of the grant are:

- A period of three years

- The return of funds that are either unspent or not spent in accordance with the agreement

- Annual progress reports and a final report are required to be given to Road Safety Authority B

- Publication of research results in conference presentations and/or scholarly journals, and

- The transfer of the intellectual property (IP) rights arising from the research activity to Road Safety Authority B.

Analysis – Is there an enforceable contract with a customer?

In this case, Road Safety Authority B is the customer as it will receive the IP rights arising from the research activity, and University A’s promise of specified research and transfer of the resulting IP is enforceable because the grant is refundable if the research is not undertaken (AASB 15, paragraph F12(a)).

Analysis – Are there ‘sufficiently specific’ performance obligations?

Judgement is required here, including whether the contract specifies, either explicitly or implicitly, the nature/type of goods or services, their cost or value, quantity, and the period over which they will be transferred to the customer (AASB 15, paragraph F20).

To be ‘sufficiently specific’, we also need to be able to determine when promises in this research contract have been satisfied.

Lastly, it is also important to remember that research activities undertaken to develop IP which will be licensed to customers are merely activities undertaken to fulfil a contract and are not ‘sufficiently specific’ performance obligations because they do not, by themselves, transfer any goods or services to customers.

This contract identifies:

| AASB 15, paragraph F20 considerations | Example 2 fact pattern |

|---|---|

| Nature or type of good or service promised | Specified research and transfer of resulting IP rights |

| Cost or value of good or service | $1.2 million value |

| Quantity of good or service | One |

| Period over which good or service is to be transferred | Three years |

Not all of the above factors need to be specified in an agreement for the promise(s) to be ‘sufficiently specific’ (AASB 15, paragraph F22). However, in this fact pattern, arguably all are present, which is persuasive in assessing that the promise in this contract is ‘sufficiently specific’, i.e. for specified research and transfer of resulting IP. It is also possible to determine when the promise to transfer IP rights has been satisfied.

University A also determines that the research services are required to develop the IP in order to fulfil the contract and therefore do not, of themselves, give rise to a transfer of goods or services to Road Safety Authority B (i.e. the research and ultimate transfer of IP are one performance obligation).

Note that the publication of research results in conference presentations and/or scholarly journals, without the requirement to deliver the IP to Road Safety Authority B, would not be a ‘sufficiently specific’ performance obligation to the customer, Road Safety Authority B.

Accounting treatment

As AASB 15 applies to this ‘sufficiently specific’ performance obligation, University A allocates the cash grant received of $1.2 million to its identified performance obligation and recognises the financial asset (cash) and a contract liability of $1.2 million on initial recognition as follows:

| Dr ($) | Cr ($) | |

|---|---|---|

| Cash | 1,200,000 | |

| Contract liability | 1,200,000 |

University A then concludes that the performance obligation is satisfied over time because the university’s performance creates or enhances an asset (knowledge – the IP) that the donor controls as the asset is created or enhanced (AASB 15, paragraph 35(b)). Accordingly, the university recognises revenue over time as it satisfies the performance obligation. The university elects to measure its progress towards complete satisfaction of the performance obligation on the basis of an input method, such as labour hours expended.

Concluding thoughts

Many NFPs defer recognition of a variety of income streams because there is a lack of clarity in the current accounting requirements for income of NFPs. However, from 1 January 2019, this situation is about to change. NFPs will need to undergo a formal assessment of all income streams to assess whether recognition under AASB 1058 or AASB 15 is appropriate. Importantly, revenue can only be recognised if there is an enforceable contract with a customer, and ‘sufficiently specific’ performance obligations. Disclosure will be required in the financial statements about key judgements made in arriving at the conclusion that performance obligations are/are not ‘sufficiently specific’. Management should therefore already be undertaking a detailed review of all contracts and agreements to determine the appropriate accounting standard for accounting for grant income.